Your works demand time and attention—two things increasingly rare on social media.Is the attention to detail, texture, and slowness of creation an implicit critique of the culture of instantaneity?

“It would be fair to read that critique into the works. Creating work in this way is an attempt to carve out a specific slowness in my life, a retreat from the overwhelming tempo of digital spaces. My paintings require time of the viewer too: details take time to absorb, and the connections and relationships take time to unfold. In this way, the paintings are probably a poor fit for a social media environment that prioritizes immediate impact and micro-attention spans. Perhaps the paintings can be a sort of refuge for the viewer as well.”

Do you see these recent works as a commentary on today’s visual saturation?

“Earlier works arose partly as a response to saturated digital environments. Around 2008 the visual density of my paintings really intensified, and at that time I was trying to capture a sense of information overload and the feeling of existing in digital spaces (ex., Data Mine, 2009, Data Centres, 2010, Confluence, 2011). Nonetheless it always felt important to me to continue to produce my paintings by hand, that my work remain grounded in material, process and labour.”

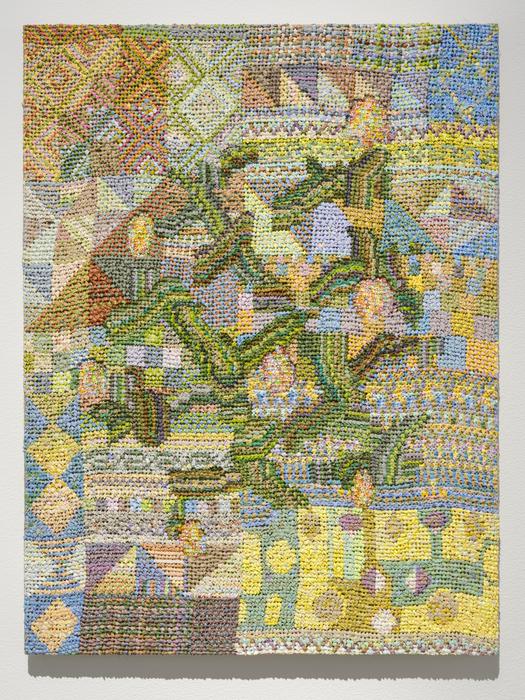

Image: Almost (Again), 2022, acrylic on wood panel, 22,7 x 17,8 cm.

What led you to work specifically with jute canvas?

“I started working with jute in 2018. During this period I was focussed on making gridded, pixel-based painting with pen and ink, but also experimenting with ways to bring a textural relief to the work. The loose weave of the jute offered a readymade grid, upon which I could add blobs of acrylic paint to build up a composition that resembled a hooked rug. The earliest of these works (ex. Beyond, 2018) were made by rolling small balls of paint with a brush, but I later switched to using syringes to apply the paint. I find the strange texture of the resulting works really compelling.”

How important is the texture or natural relief of jute in the final composition?

“I’ll often apply the jute to the panel with a gentle bend or wave, giving the grid a flow like a loose fabric. Sometimes I let portions of the jute show in the finished composition to create material contrast, and I always leave the wrapped sides of the panel exposed so that the jute is visible. Its presence helps to establish the relationship with textile that I’m playing with in the work.”

Off Grid, 2025, Acrylic on burlap on wood panel, 61 x 45,7 cm.

What are you seeking to express through this combination of materials? Is it a way of reconnecting with materiality in a digital world?

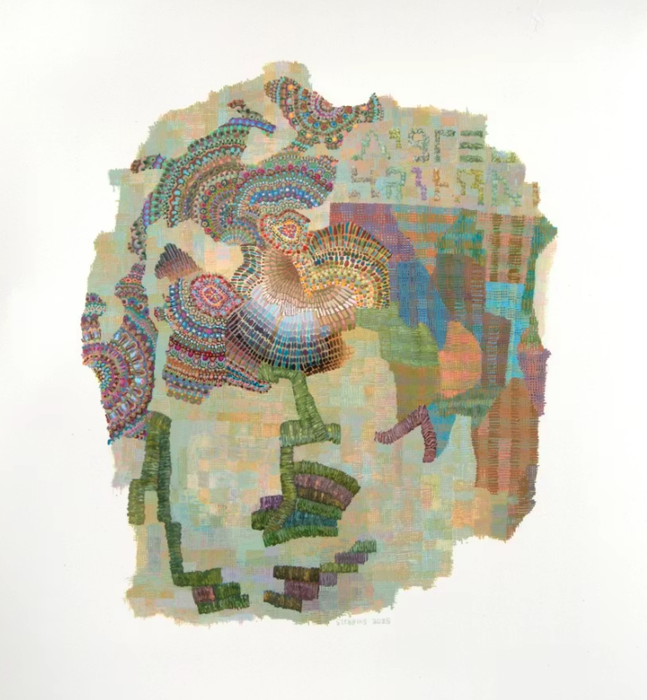

“That’s exactly it. My work has always been materially grounded, and I’ve been fairly insistent on making paintings by hand, that they hold nuance, imperfection and a relationship to human labour. But lately, with the push towards so-called AI and a world that is increasingly saturated with digital media that is not only dematerialized but also synthetic (that is, not created by humans), I find myself wanting to retreat to a greater embrace of materiality. In some cases this has involved thinking about the production of historical textiles. For example, Borerlines and The Place, both 2024, make reference to specific 19th-century embroidery works in the material culture collection of Museum London, but painted with an exaggerated materiality. This Thing, 2025, strips away any specific reference and foregrounds the materiality declared in the title. With the omnipresence of art on social media, it’s easy to forget that paintings are real things, and need to be approached in the real world for the full experience.”

What inspires the complex patterns and intricate structures in your work?

“I like paintings that open themselves up slowly over time and continue to offer mystery and the possibility of discovery. The paintings are static but the relationships between the abundant details slow down the reading.

More specifically, I’m endlessly compiling a wide variety of visual research which gets reflected in my work. This includes historical and contemporary textiles, quilts, embroideries, tapestries, diagrams, flowers, botanical drawings, snapshot photography, pixel art, digital and analogue glitches, and of course, broadly, historical and contemporary painting.

Up until recently, I tended to work in an impressionistic way in relation to these sources. They would get filtered through my imagination, a kind of background to the ideas I’d be trying to connect in a painting. While engaging with the collection at Museum London for my recent exhibition there, I found it more interesting to respond specifically to particular works, mostly 18th and 19th century embroidery samplers from Southwestern Ontario. I’d study the pieces in detail, repeating or adapting some of the motifs as a way to make connections across time (example, Mackie’s Birds [Remix], 2024, Echoers and Off Grid, both 2025).”

Image: Recollector, 2023, acrylic on wood panel, 25,4 x 20,3 cm.

What role does chance play in your creative process?

“My creative process tends to vary substantially from piece to piece. Painting has always felt like a form of thinking to me, a way of sustaining focus and developing ideas slowly over time. Drawing sketches and studies has always been foundational in my practice, but improvisation has been equally important. Some works take extensive planning, particularly the photographic or patterned ‘pixel’ paintings (e.g., Passing, 2018 or Bloom, 2020), but even these involve a degree of improvisation and flexibility. For me, too much pre-planning can kill the vitality in a work. Some paintings begin as pure improvisation; I’ll start with only a loose idea then let the slow, circular process of painting-thinking-painting allow the work to take shape, little by little. If a work is starting to feel too predictable, I’ll sometimes switch to making marks in a more intuitive mode to help me arrive at an unexpected result. Many works take shape over a period of years alongside other works in my studio, undergoing transformations in the process that allow them to develop in ways that surprise me. In the end, a work should reveal something new.”

Are there particular artists, writers, or thinkers who have shaped your artistic vision of the world?

“It would be impossible to give an exhaustive list here. I’m a collector of images (books, magazines, digital files) and for decades I’ve been compiling folders of images of art that has inspired me.”

How do you envision the evolution of your work in the coming years: a return to digital media, or an exploration of new materials?

“I’m still experimenting with the possibilities of jute and I foresee a further embrace of texture and materiality in the work. I’ve also been making works on paper (ex. Echoers and Shards, both 2025) and window screens (for example, Mono No Aware, 2018, Sampler, 2023-24) and I’ll probably continue with these.”

Do you plan to further combine digital techniques (AI, etc.) with traditional materials such as jute or textiles?

“I actually use digital technologies fairly often in my work. I’ll sketch or test ideas, compose pieces or manipulate photos to prepare for a painting. This is often happens in parallel to my physical painting process. I actually did a few fully digital works for my 2019 exhibition Oblivion Souvenirs. These were essentially ‘digital quilts’ composed of hundreds of scans of textiles and clothing from around my house, and they were output as limited, archival inkjet prints (ex., Unremembering, 2018). At the moment, though, I’m more interested in pursuing the possibilities of material, handmade work.

I’m not a big fan of ‘AI.’ Painting for me is an intellectual process, one that results in the creation of physical objects that embody and express that cognitive labour. Delegating any part of this to a machine would rob the work of its richness, humanity and value.”

View of the exhibition “Echo Choir”